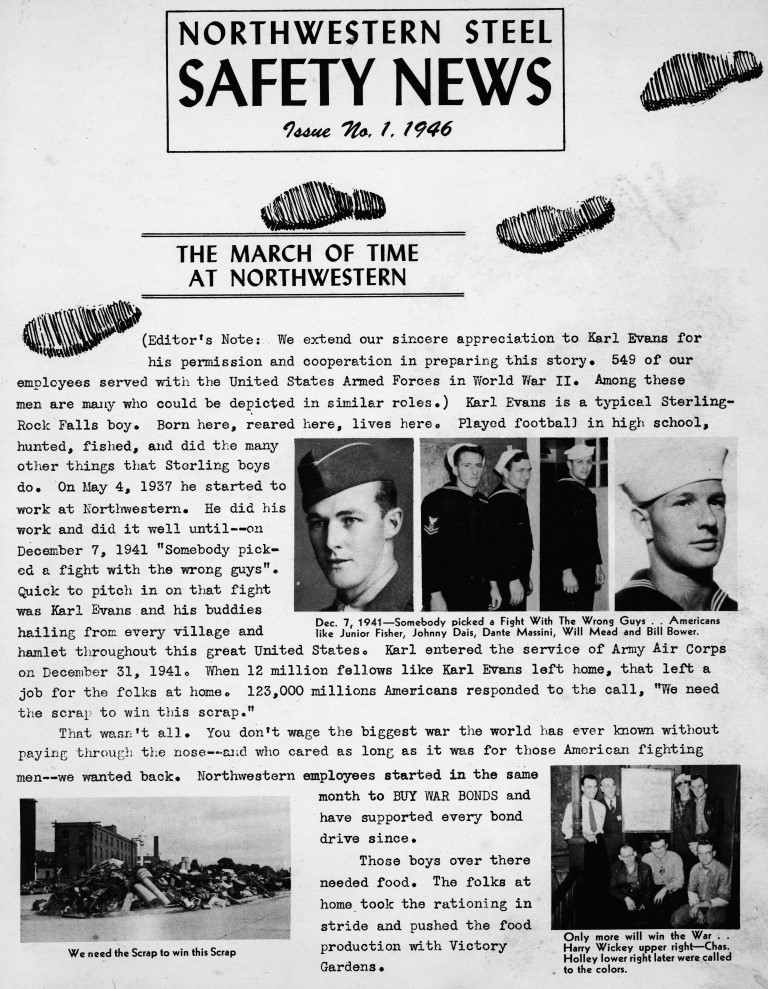

This is a copy of the ‘Safety News’ that Northwestern Steel & Wire published for many years. On page 3 there is the story of Karl Evans, who worked as a gauger on the 10” Mill. Karl was in the service during World War II and ended up being a prisoner of war. He was in Europe for a total of 27 months, returning home on October 1, 1945. Page 3 and 4 of this newsletter make for some very good reading.

Blog Archives

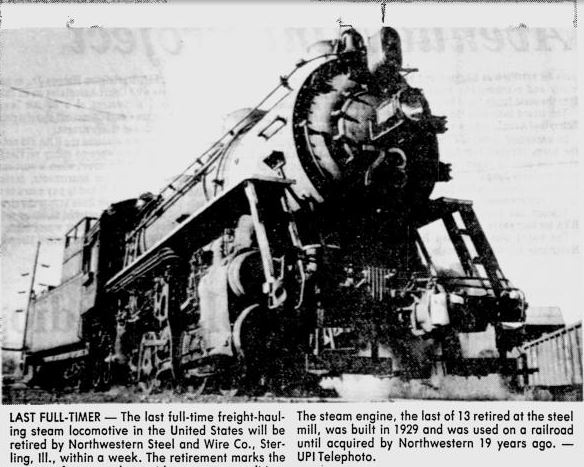

Steam Locomotive to Be Retired, Published 1980

Published by UPI in December 3, 1980

Steam Locomotive to Be Retired

Sterling, Ill. (UPI) – The last continuously operating iron horse is being put out to pasture, marking the passing of another of the steaming marvels that opened the West.

In retiring the last of its freight-hauling steam locomotives, Northwestern Steel and Wire Co. ends a stubborn company tradition.

Northwestern, a steel mill sprawled along the banks of the Rock River, began using steam engines in its switching yards in the 1050’s and has used them ever since.

When most companies switched to diesel engines years ago, Northwestern’s president – the late Paul W. Dillon – was a loyal steam engine buff who refused to follow the crowd.

But now, bowing to economic pressure, Northwestern has announced the last of its iron horses – a 100 ton, jet-black beauty called No. 73 – is being put out to pasture.

No. 73 was built in 1929 and worked for Grand Trunk Western Railroad until it joined the company 19 years ago. Its replacement diesel is to be on the line by Monday, when the proud, old steamer will join 13 other old-time locomotives in the company’s iron horse pasture.

One of the locomotives will retire to a Sterling museum – the mansion of the late Dillon – but company officials are not sure what will happen to the others.

“We don’t want to melt them down,” a company spokesman said. “We are trying to find some good homes for them.”

Only five of the old steamers are still in good working condition.

“This is the last of the grand era of steam,” said Jim Boyd, editor of the Rail Fan & Railroad Magazine. He said Northwestern Steel and Wire was “the last continuously operating vestige of the steam era.”

Boyd, an authority on the subject, said only one other company – Crab Orchard & Egyptian Railroad of Marion, Ill., – uses steam locomotives continuously for hauling freight. It originally used the engines as a tourist attraction but covered them to freight use in 1977.

“But none have the continuous freight operation that is the heritage of Northwestern,” Boyd said.

The engines’ retirement may be nostalgic to railroad buffs, but steel mill engineers are not sorry to see them go. Diesel engines will be easier to maneuver and repair, they said.

“Nostalgic? No as far as with work goes,” said Gene Genslinger, who engineered 16 years before becoming general foreman. “Some people told me they would do my job for free. I said, ‘Not for long!’ We were broke down all the time. We fought ‘em for years.”

Northwestern Steel & Wire Co. said it lost $58.3 million / Article from 1997

Northwestern Steel & Wire Co. said it lost $58.3 million.

September 12, 1997 | Chicago Tribune

Northwestern Steel & Wire Co. said it lost $58.3 million, or $2.34 per share, in its fiscal fourth quarter, a reversal from a profit of $9.9 million, or 40 cents per share, a year earlier, when fewer shares were outstanding.

The Sterling, Ill.-based mini-mill said sales in the quarter, ended July 31, inched up 1 percent, to $180.4 million from $177.8 million.

Northwestern Steel said excluding a charge related to the closing of its Houston structural mill during the quarter, the company earned $1.5 million, or 6 cents per share, in the latest quarter. Excluding tax benefits of $8.8 million, or 35 cents per share, the company earned $1.1 million, or 5 cents per share, a year earlier.

For the fiscal year, it said it lost $63.1 million, or $2.54 per share, compared with net income of $20.7 million, or 83 cents per share, a year earlier. Sales fell 3 percent, to $641 million from $661.1 million.

Northwestern Steel And Wire Agrees To Takeover / 1998 News Article

Of course this deal fell apart and this never did happen.

__________________________________________

Northwestern Steel And Wire Agrees To Takeover

Tentative Deal Seen As Way To Save Jobs

February 14, 1998 | Chicago Tribune Staff Writer.

Northwestern Steel and Wire Co., which only recently has begun rebounding from a long slump, said Friday it has tentatively agreed to be taken over by a Southern steelmaker in a cash-and-stock deal valued at roughly $240 million.

The takeover would mean the disappearance of an Illinois corporation that dates to 1879, but the companies said it may help secure the jobs of Northwestern’s 2,100 employees in Sterling, about 100 miles west of Chicago.

If Northwestern reaches a definitive deal with Bayou Steel Corp. of La Place, La., the companies said they would spend more than $100 million to replace a mill that makes structural steel with a new mill with almost twice the steelmaking capacity.

The companies also said they would leave in place Bayou’s mills near New Orleans and Knoxville, Tenn., as well as its Chicago warehouse.

“No one is going to come in with a meat ax,” said Timothy Bondy, Northwestern’s chief financial officer.

But while employees may embrace a merger, Northwestern’s shareholders may be hoping for better terms. Unlike most takeover proposals, Bayou Steel’s bid for Northwestern did not include any premium for the company’s shares.

At most, Northwestern investors would receive $2.29 in cash and $1.71 worth of Bayou stock for each Northwestern share, or $4 altogether. That is below Northwestern’s closing price of $4.44 a share on Thursday.

Northwestern shares dropped 81 cents on Friday, to $3.62, on the Nasdaq stock market. Bayou shares rose 69 cents, to $6.44, on the American Stock Exchange.

At $4 a share, Bayou would be paying $100 million for Northwestern’s shares. It also would assume Northwestern’s debt, estimated at $140 million.

Northwestern–a mini-mill that makes steel by melting scrap steel in electric arc furnaces–has had a rough time over the last decade. A management-led group bought the company in 1987, but foundered after acquiring a money-losing mill in Houston.

Northwestern was on the verge of bankruptcy in 1993 when Kohlberg & Co. bought a controlling interest for $35 million. The company re-emerged as a publicly traded firm a year later, with Kohlberg retaining a 35 percent interest.

Even in the strong steel market of the 1990s Northwestern has been only marginally profitable. Since 1990, Northwestern has lost a total of $85 million, including a $63.1 million loss in fiscal 1997, which ended July 31.

But last spring, Northwestern brought in a new chairman and chief executive–Thomas A. Gildehaus, who had just restructured UNR Industries Inc.

Then, last summer, Northwestern closed its Houston mill, firing 325 employees, and last fall the company recorded its best first-quarter results since 1993, a profit of $7.8 million on sales of $138.9 million.

Northwestern’s survival is also important to Unicom Corp.’s Commonwealth Edison Co.

With its three 400-ton electric furnaces, which are among the largest in the world, Northwestern is Edison’s single biggest power customer.

The Story of Northwestern Electric Furnace Steel ~ Slide Notes

Sometime during the 1970’s or so, Northwestern Steel & Wire Company put together a 40+ slide show that showed the history of the Electric Furnace. I have found a copy of the slide-show notes but not the slides themselves. I have waited and looked for about two years but I have pretty much given up hope of finding someone with the slides so I am posting the slide-notes in hope that it spurs some interest and someone might know where a set of the slides might be. I do think that there are enough other photo’s to reconstruct about 1/2 of the slide show from other photos. Either way I think these slide-show notes are interesting.

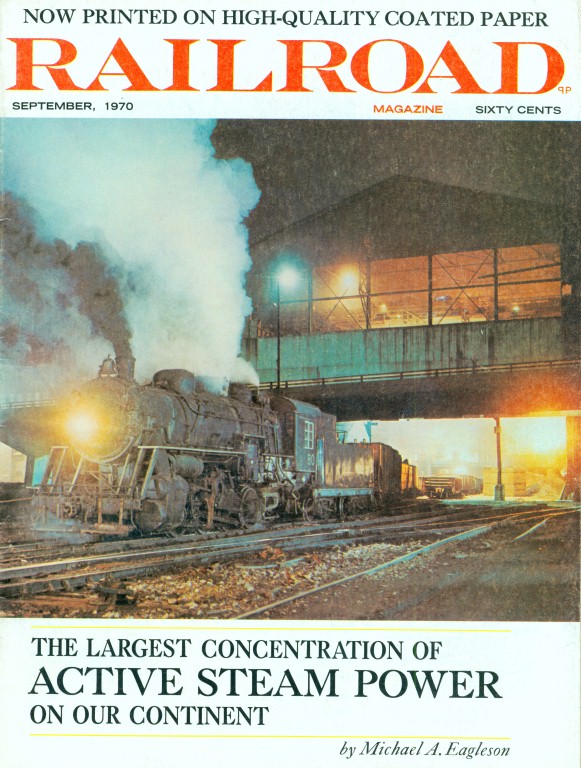

September, 1970 ~ RAILROAD Magazine

December 2011, I purchased a copy of RAILROAD Magazine off of eBay. The issue was from September, 1970. There was a neat article in it about Northwestern Steel & Wire and the use of the steam engines. Here is that text and some pictures of that article.

THE LARGEST CONCENTRATION OF ACTIVE STEAM POWER IN NORTH AMERICA

photos and text by Michael A. Eagleson

It was pouring rain as I stepped off a bus at the Dixie Hotel in Sterling, Illinois. After bouncing for an hour and a half through the night from Chicago, my thoughts were not on steam but on getting a room and some rest. This was the first of my five visits to the largest concentration of active steam power in North America today, and I wasn’t sure what I would find.

In the morning, I headed for the railroad yards at a fast walk, grumbling over the dreary wet weather. Once inside the visitors’ entrance to the Northwestern Steel & Wire Company, I was greeted with: “Oh, you’re another guy come to see our steam engines. Just wait here and we’ll fix you up.”

I sat down, listening to telephones ring and watching cute little mini-skirted secretaries on their way to the filing cabinets and the water cooler. At length a man handed me a release to read and sign, asking: “Where are you from, boy?”

“New Jersey,” I replied.

“We get ’em from all over. Last month we had a pair ‘from England. Damn if I know how they hear about us. You guys must be crazy to come so far just to see a bunch of dirty old steam engines.”

“Yes,” I said unconvincingly, anxious to get out of the office and on to the object of my own crazy thousand mile” plus journey.

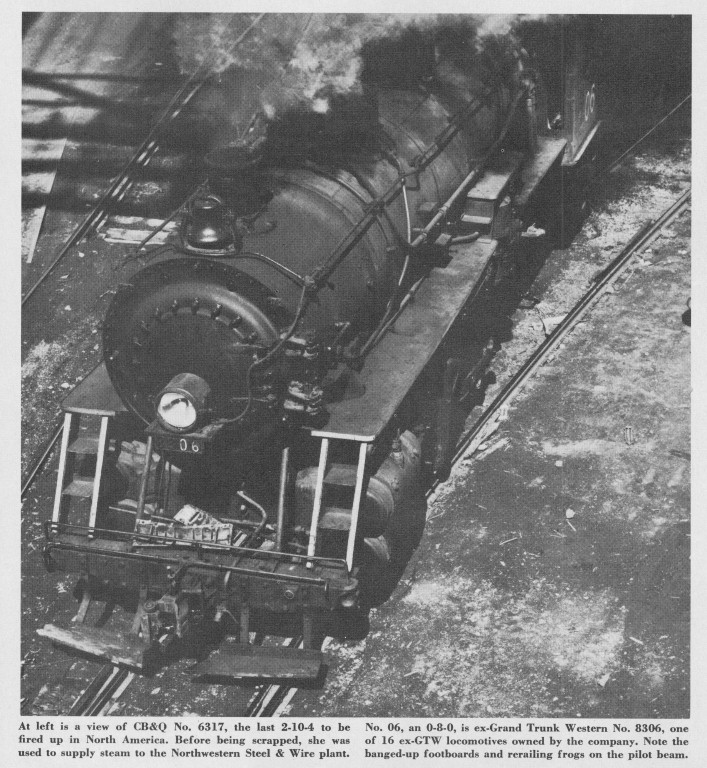

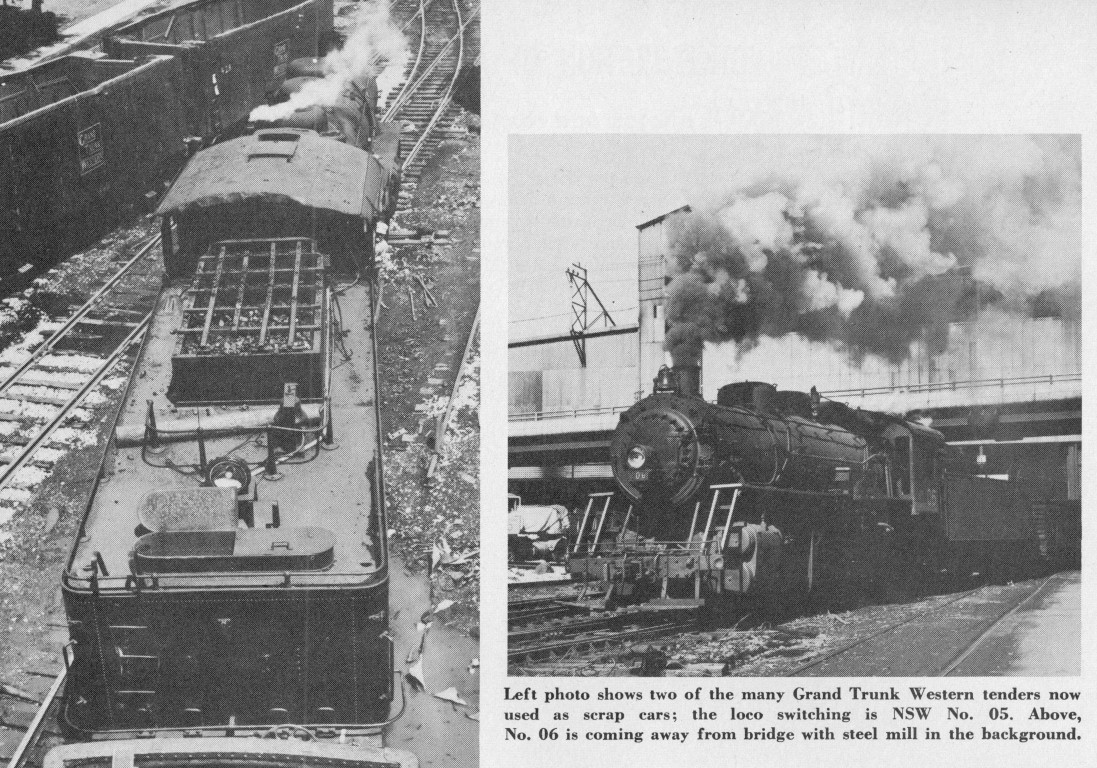

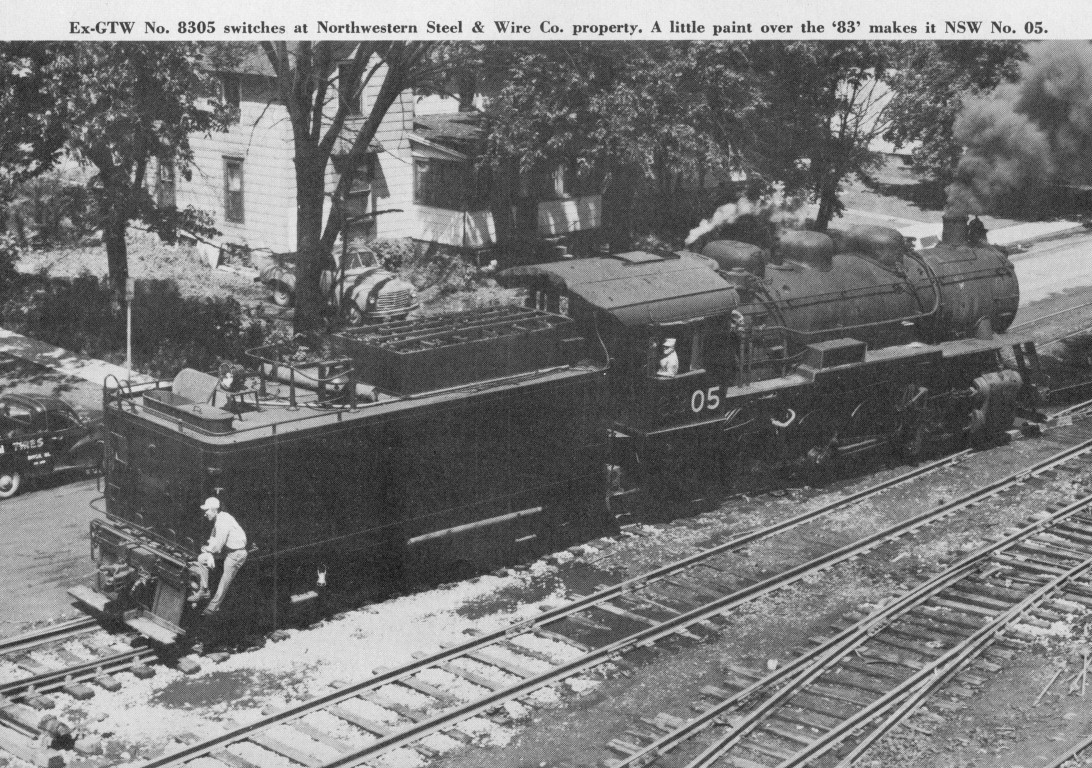

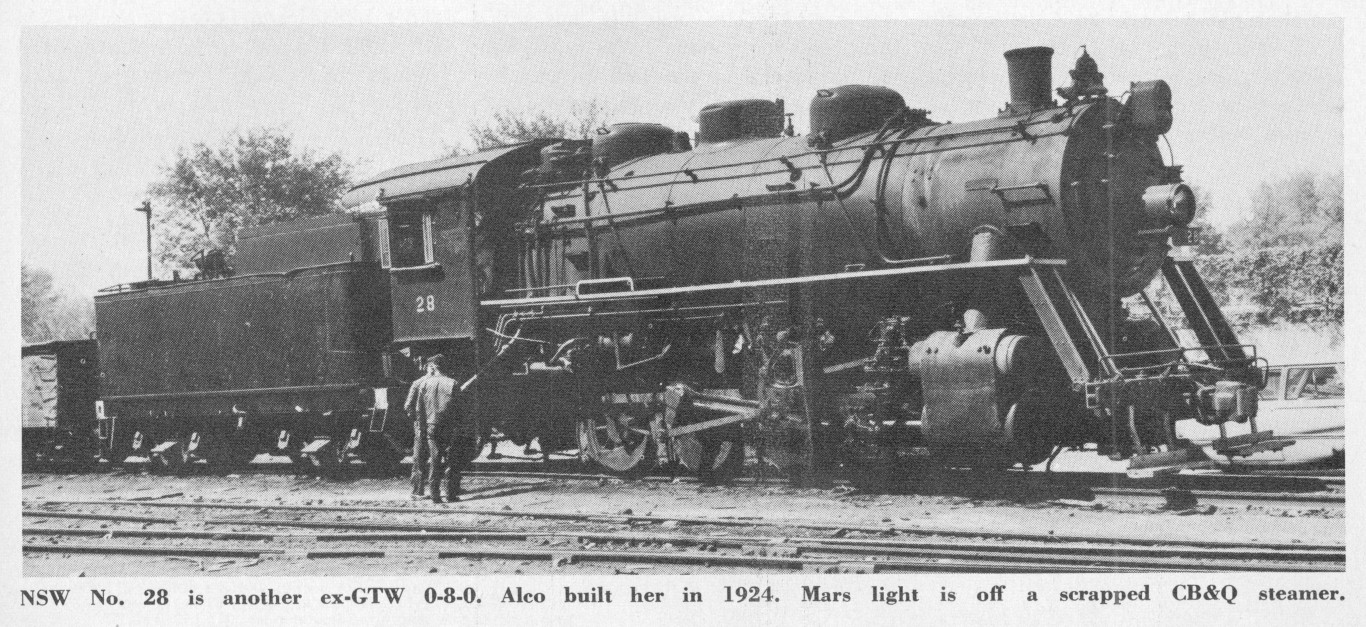

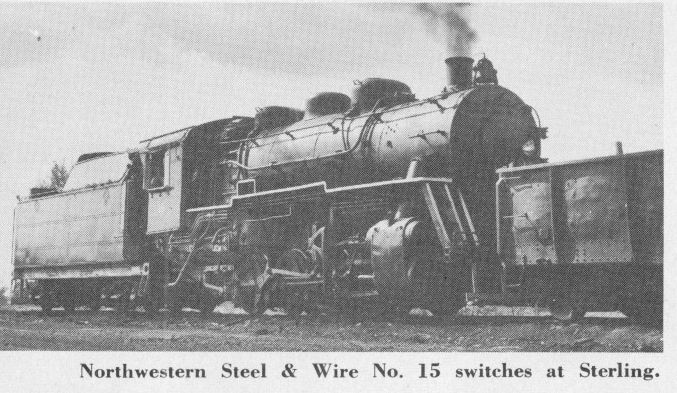

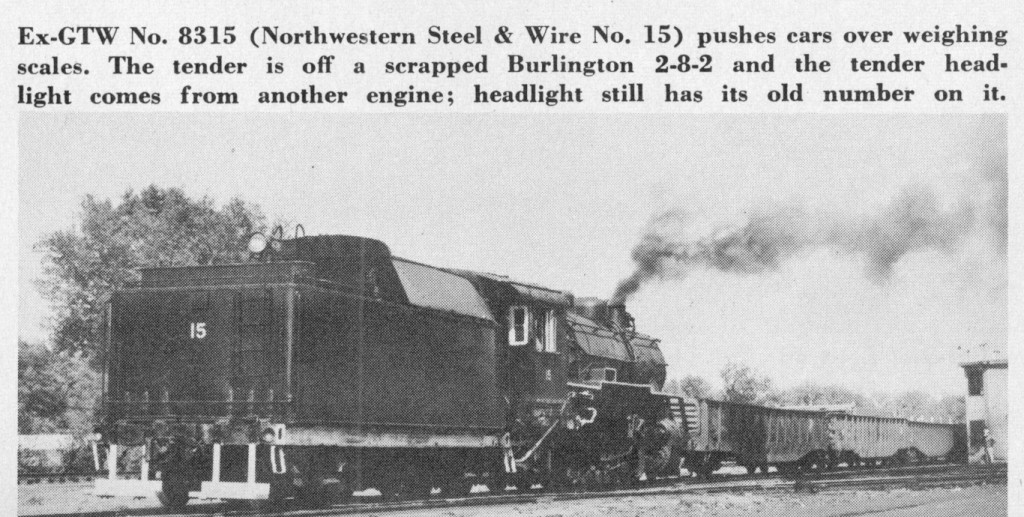

With a visitor’s pass visibly sticking out of my breast pocket, I walked over to the engine terminal. My eyes fell on six ex-Grand Trunk Western 0-8-0’s coupled dead in engine-to-tender fashion. Their parental heritage was obvious to a steam enthusiast; but there was something odd about the oscillating Mars lights from scrapped Burlington steamers, mounted above their headlights where the typically Grand Trunk Western V-shaped illumination boards used to be. Oh well, they’re steam, I thought, and moved on.

Just beyond, rose a square water tower, apparently made from a discarded engine tender, and beside it stood No. 05, another husky 0-8-0, but this one was alive. As I approached to examine the switcher more closely, she startled me by suddenly popping off. Almost simultaneously, an armed guard grabbed me, growling that I was on “company property.” I pointed to my visitor’s pass, but he shouted over the roar of the escaping steam: “You know, that’s only good for taking pictures on city streets. You can’t enter our property.”

Slinking away behind a crossing shanty with rotten and warped clapboards, I mused disconsolately over the excellent photo I almost had taken before this confrontation. No. 05 had quit popping off now and was being stoked. Her thick black smoke faded.

Slinking away behind a crossing shanty with rotten and warped clapboards, I mused disconsolately over the excellent photo I almost had taken before this confrontation. No. 05 had quit popping off now and was being stoked. Her thick black smoke faded.

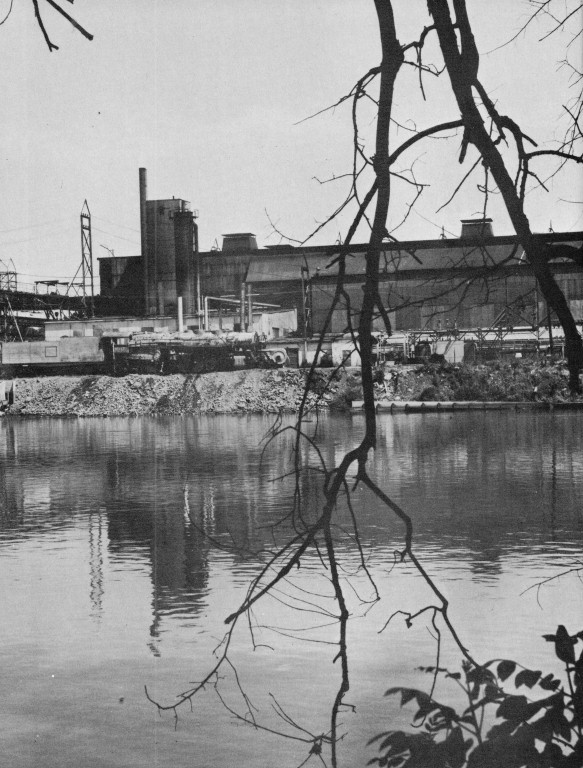

Wandering down the street that paralleled the tracks, I spotted another hot engine. She was resting directly underneath a highway bridge that crossed Rock River, connecting Sterling with Rock Falls on the opposite bank. White vapor leaked profusely from every joint of the loco, which I knew that Alco had built in 1924. Climbing onto the bridge and assuming a sentry position, I waited in the drizzle for some action.

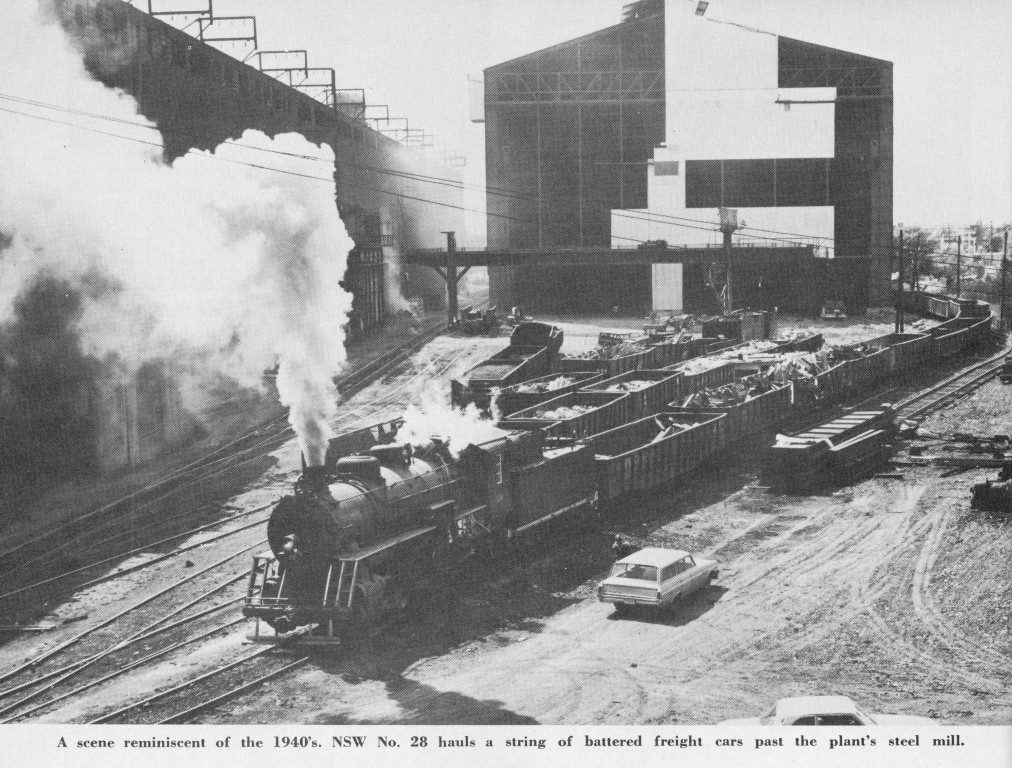

Ten minutes passed. Then I heard the first groan of the engine brakes releasing. The switcher slipped her 51-inch drivers on the wet rail while starting a long string of freight cars into the very heart of the steel plant. Her 45,175 pounds of tractive effort dug in. Her exhaust grew faster and louder, with the” echo reverberating from nearby buildings. She was in regular service. No fake Indian raids, Jesse James stickups, or kids and tourists looking at an oldtime steam train. This was the way things should be, and I was glad to be there. I enjoyed listening to the tones of her grime-covered brass bell. The old familiar bark of a big engine hard at work brought music to my ears. I was so enthralled that I scarcely noticed the beads of rain water spotting my camera lens or the hot cinders soiling my light tan jacket. This was why I had come to Sterling-to see and hear and remember.

No. 06, ex-Grand Trunk Western No. 8306, has kept working almost ten years after the brass collars had said she was obsolete and must go. How reassuring it is to see steam in regular service!

Northwestern Steel & Wire Company has a long history of being switched by steam. P. W. Dillon, the board chairman, grudgingly admits his affinity for steam locomotives. Mr. Dillion, now in his eighties, says they are good for at least another ten years, but I doubt it. Replacement parts are almost impossible to get today. Such items, as a rule, are either scavenged from the out-of service spare 0-8-0’s or made by NSW shopmen under the supervision of chief shop mechanic Larry Cain. He and his three assistants are responsible for keeping the herd of steamers running.

Even so, Dillon’s main argument at least to his board of directors-for keeping the steamers so long is purely economics. Yes, I said economics! Steam is accused of being expensive to operate, particularly in yard service where much time is spent in just sitting around. This is not true at Northwestern Steel & Wire.

“A diesel switcher, a new one, costs $180,000,” Mr. Dillon says. “We’ve got mountains of scrap iron around here, and, if the diesels brush against them the traction motors are likely to be damaged. And when one of them derails, there would be damages, too.”

Not so with steamers. They can bump into obstructions, or stub their toes and derail, but keep right on running with a minimum of repair. Evidence of this is seen in the mangled footboards on the plant’s engines. They are, you might say, battle scars.

Northwestern has always used steam, usually hand-me-down switchers. In the late 1940’s it had little ex-CB&Q 0-6-0’s. Next came 0-6-0’s from the Illinois Central and the Chicago & North Western, and finally ex-Burlington USRA types with the same wheel arrangement.

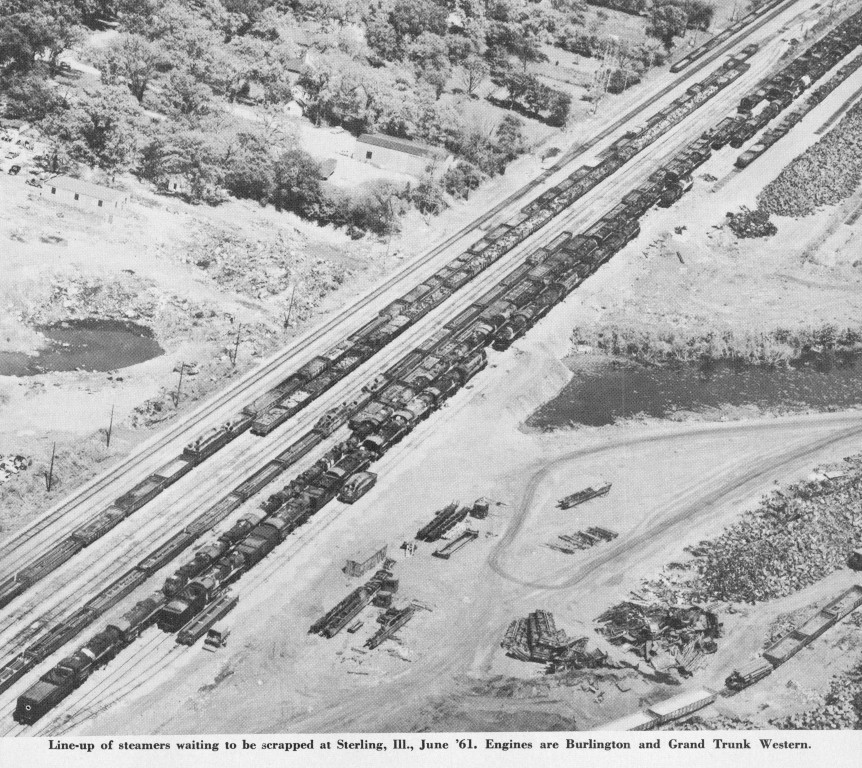

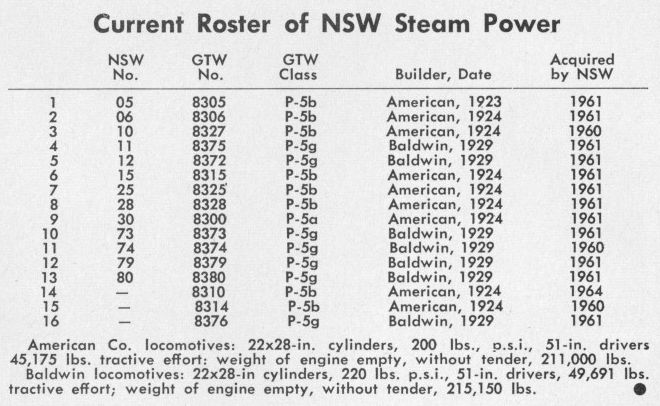

The 16 former Grand Trunk Western steamers that are now being used arrived in 1960 and 1961 when that road was on a steam-scrapping spree. They were intended to be dismantled along with hundreds of other steamers from the Nickel Plate, the GTW, and the Burlington. Someone wisely noticed what good shape these 0-8-0’s were in, compared to the smaller power then being operated and decided to save them, popping their own power into the ovens instead.

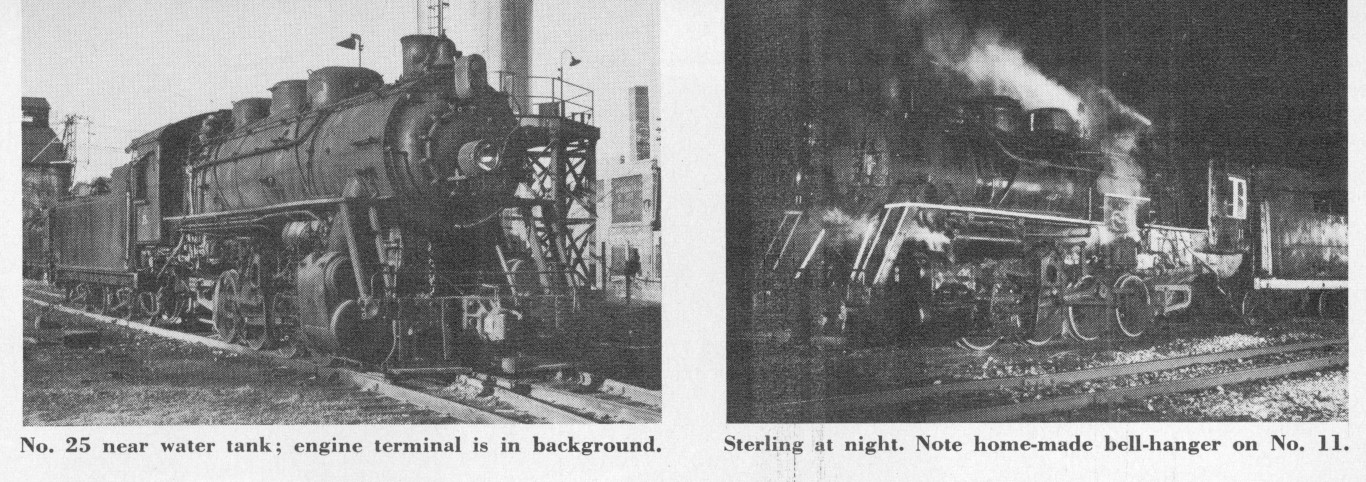

Today, the company has several miles of track lined with dangerous debris. The plant usually works two or three steamers through it for seven days a week, 24 hours a day. The locos haul scrap to furnaces and haul finished products to the shipping stations and weighing scales. The plant connects with the Chicago & North Western, and its steamers briefly venture out daily on their iron to pick up or drop off cars.

The company uses dozens of tenders off scrapped Burlington 4-8-4’s and 2-1O-4’s and GTW 2-8-2’s. The tenders have had their coal bunkers and water baffle plates removed. The cars are now big open-top shells, but still sport the heralds of their former owners. Since the tenders have couplers only at one end, they are cleverly connected in units of two, drawbar to draw bar. They can be separated for switching only at the ends with the knuckle couplers.

As late as 1962, Northwestern had more than 100 steamers from various roads laying, around, awaiting the cutting torches and smelters. On my first visit to Sterling in 1963, I found Burlington 2-1O-4’s and 4-8-4’s, Grand Trunk Western 2-8-0’s, 2-8-2’s, 4-6-2’s, 4-8-2’s, and 4-8-4’s, and even some NKP Berkshires awaiting the torch. Grand Trunk Western 4-8-4 No. 6322, of fantrip fame, was rusting away with “Farewell to Steam” still chalked on her rusted Vanderbilt tender. Nickel Plate Berkshire No. 730, which was often used in public relations and press release photos during the railroad’s steam-conscious 1940’s, stood beside the others, awaiting the same fate and a reprieve that never came.

For a while during the early sixties, NSW saved bells, headlights, whistles, number plates, and builder’s plates from the engines, selling the booty to trophy hungry fans who hated to see their favorite locomotives scrapped. Today, all such parts have long since been cleaned out, as well as the Burlington’s first 4-8-4, No. 5601, class 05a. In 1963 I sadly watched her being cut up. Today, only the GTW switchers remain, due to their usable wheel arrangement. Once a pair of 600-hp. EMD units were bought second-hand and tried out. They proved too frail, as diesels can’t work under these conditions. Finally they were taken off their trucks. Inventive Northwestern used the diesels as emergency power units behind the mill, and applied the traction motors and trucks to a roving gantry crane.

It’s hard work keeping, this railroad operating. Northwestern employs 24 trainmen, a track crew, and a maintenance crew to keep the miles of track, 16 steamers, and dozens of cars running. Daily the steamers consume up to 24 tons of coal and 48,000 gallons of water. Then, of course, the fires must be serviced for changes in crew.

A major problem affecting the NSW operation is the enormous amounts of sharp, twisted scrap metal lying about. Anyone could easily get hurt around all this junk. Because of it, engines and cars jump the track almost as a routine matter. In fact, I have seen cars being pulled about with 20-foot bands of bouncing, swinging steel slapping about the car sides, wrapped around the wheels, and lashing out at switch-stands or anything it passed. Since only the locomotive’s brakes are used (the car brakes are not working), stopping for an emergency is quite difficult, and sometimes the cars bang into the back of the tender or wrench a drawbar.

For these reasons, I understand the extreme insurance restrictions and the often hostile guards working for, the safety-conscious Northwestern. I was personally escorted out of town and over the bridge into Rock Falls the night I made the cover photo used on the current Railroad Magazine and the other night shot illustrating this article. The plant guards, wearing yellow safety helmets and steel-toed shoes, felt that I had overstayed my welcome and visitor’s rights by hanging around after dark and firing off several dozen flash bulbs. Perhaps I was lucky, however. Many fans have found out that in taking photos without a permit you run the risk of having your camera or film confiscated. A fan should show the courtesy and the small effort it takes to get such a pass, respecting the wishes of a company which is currently using 16 steam locomotives.

Recently, health-conscious citizens of Sterling have been up in arms about the smoke that NSW is adding to the atmosphere. As a result, the steamers appear to be scapegoats. Mr. Dillon wants his company to try and replace coal with natural gas, condensed into liquid form as fuel.

“Then the engineers could come to work in white shirts,” he says.

The engineers, incidentally, run the locomotives without firemen, doing their own firing while switching cars.

Last spring, the Railroad Club of Chicago had the first organized fan trip to Sterling to see the steamers, and found 0-8-0 No. 25 operating with an ex-Kansas City Southern Vanderbilt oil tender, coupled backward behind her! Evidently the company is trying oil as fuel for a while. Once chief mechanic Larry Cain experimented with diesel fuel oil in place of coal in a steamer.

“That didn’t work out,” he recalls. “For one thing, so much fuel was gulped up in the firebox that we were refilling the tank every half-hour.”

Once before in 1964, Northwestern fired up oilburners. It converted two Burlington 2-10-4’s to burn oil and placed them behind the mill, with rods off and a huge smokestack attached. The hulks supplied steam to the plant for a while. This operation has ended now, and the gallant Texas types were put to death in the mill which they had served. These were the last 2-10-4’s fired up in North America!

As of now, the steamers look as if they will be used for a few more years, but don’t count on it. I have seen overnight changes in management’s policy to do away with steam power on other all-steam roads. But as long as Mr. Dillon wants to hear the beloved sounds of steam locomotives echo through his steel mill, there will be smoke and steam over Sterling.

Floods and Fires at Northwestern Steel & Wire Company

No Work Stoppage At Northwestern Steel & Wire Company During Major Floods and Fires Of 1938.

Employees Pitch In To Re-build After Disastrous Flood Of 1938

Retrieved from The Daily Gazette ~ March 13, 1979 Edition

Transcribed, and minor corrections made, by Dana Fellows ~ 2011

Two major fires in 1928 and 1939 along with a flood in 1938 caused extensive damage at te h Northwestern Steel & Wire Company but in all three events, no work stoppage was reported and the employees played an important role in the reconstruction which followed.

Fire is an ever present hazard in a steel mill and the first of the two major fires which hit Northwestern occurred on Friday, May 18, 1928. The fire was a result of some necessary welding from a platform under the wire mill.

Gears in the fence machines above were driven by shafts which extended down through the floor to the platform . Millwrights would bring barrels of grease from which they would throw grease into the gears as a lubricant. Surplus grease would fall unto the platform and also on the ground below and this waste apparently was not cleaned up.

So, on Friday, May 18, 1928, a torch was being used by welders (Chapman Brothers) set the grease afire. A witness, Gorge Pulford, reported he was coming around a furnace, when, Whoosh!… it went up just like that. Authorities indicated the wind on that particular date helped the fire along.

Pulford recalled that he was one of the several men who turned on hoses where the elevator shaft is now located. “Sandy” Hill and Bert Bradley, chief engineer, also helped with the hoses.

“All of a sudden, there was a big crash, “ Pulford said and added, ‘up on the third floor were these great big furnaces machines, much heavier than the ones we have now. When the floor let loose, down came those machines… boom? We all dropped our fire hoses and ran for the river,…there was no other place to go.”

The fire of 1928 claimed three lives and property damaged estimated at $250,000. The three who lost their lives were working upstairs. One of them would have gotten out safely, but he went back to get his watch in the cleaning house, where the men usually left their watches at that time.

No Work Stoppage

Paul W. Dillon was in Chicago at the time of the fire and when informed, he chartered a plane and returned to Sterling. As he circled over the mill to assess the damage before landing, he obviously was thinking ahead… not bemoaning what was now in the past.

In a report carried in the Sterling Daily Gazette newspaper the afternoon of the fire, it featured a good news item…. “Work for all employees”… contrary to advance reports that the mill would shut down., and the account further indicated., “every employee will be given work and should report Money.”

P. W. Dillon and the mill staff had immediately made the decision to rebuild in the wake of the disaster. In this, as in other emergencies, Northwestern employees were used as a labor supply for the re-construction which followed, rather than bringing in outside help – at least any more than was necessary for specialized work.

During the re-building, office workers also continued at their jobs while the new building was erected and machinery installed. A major changed resulting from the fire was the replacement of water power to the more modern use of electricity supplied from Northwestern’s own steam driven turbines.

A major fire struck northwestern for the second time, 11 years later on Money, March 6, 1939. The 1939 fire started in electric wiring in the bale tie department and was discovered around 6 AM the fire spread and was quickly out of control and reared through the bail tie, barbed wire, machine shop and the galvanizing departments before it was finally checked.

All area firefighting equipment was at the scene including the units from Sterling, Rock Falls and the city of Prophetstown. Firemen fought the blaze despite low water pressure which hampered their efforts. The water used to halt the blaze was pumped from the mill race which still existed although no longer used for power at that time.

Employees near the scene reported seeing the black smoke rolling up as they came to work, then seeing Paul Dillon as he stood in the street directing fire trucks to their locations. No one was injured seriously and the fire was under control by noon.

As in 1928, the decision to rebuild on a larger scale was made before the flames were completely out and that information formed the lead paragraph in the afternoon news report of the fire. It was especially important to get back into production quickly as demand for wire products is heaviest in the spring.

Even though the fire loss was covered by insurance, it was more heart-breaking experience added in other major problems. The 1939 fire came a year after a disastrous flood. The company was still struggling with the adjustment to a unionized work force and had not fully recovered from the financial strains in the installation of the electric furnaces and mills in 1936.

Employees Assist

But, despite the stormy labor relations of the period, men worked night and day shifts to get the mill back into production. The fledging union offered to work one day without pay each week for four weeks to facilitate rehabilitation of the plant but the offer was declined with worm words of gratitude, NS&W President James C. Foster expressed the intention of the management to provide employment for everyone affected by the fire.

Various employees at that time recalled other items in the efforts to rebuild the mill.

By three o’clock in the afternoon of the fire of 1939, a new conveyor had been built over the ruins and was carrying fence to the shipping department for loading.

Two of the bale tie machines were still operable. A tarpaulin was put over them and men kept on working. It was cold; ice froze on the wire coming from the furnaces.

Railroad cranes were used to pick up the damaged machines and transport the equipment to the Parrish-Alford plant in Rock Falls. There the machines were repaired and returned to Northwestern.

As the building frame were up and there were places to set up the machines, they were placed into operation again even though the ends of the buildings were still open, enclosed partially by tarpaulins.

Until the galvanizer could be re-built, galvanized wire was purchased from the American Steel and Wire Company in order that Northwestern customers could be served. But even rebuilding the galvanizer didn’t take too long; as soon as the frame was ready, it was set up and made ready for wire production again.

There was a great deal of improvising. For example, railway car sills were used for columns. Anything available was used to re-build in a hurry and get back into production. Resumption of operations was further speeded up by the loan of a battery of surplus barbed wire machines by Jones & McLaughlin.

The flood of 1938

In February of 1938 ice in the Rock River broke up and formed hue jams in tans below the Sterling-Rock Falls area. The ice jams dammed up the already swollen river until water began coming over the retaining wall into the Northwestern plant.

When it became obvious that the mill would be flooded, men began shutting own equipment and pulling up motors. Water along with ice poured into the 10-inch mill and also the furnaces, mold pits, the wire mill and the basement of the office building. Office workers in the basement moved up to the second and third floors but there just wasn’t room for everyone. Elmer Hook recalls coming to work that particular day and seeing his desk out in the middle of the street.

Row boats were the only means of getting around the plant and little could be done until the water receded. One employee recalled seeing some of the men spearing carp, which had been card in the flood water, to an area near the office building.

Efforts were made to dynamite the ice jam without much success; but when the gorge did break loose after a week or so; the water literally went down overnight.

What was left in the wake of the flood was a sickening mess. Mud covered everything. Pools of water stood in all low spots. It was now a “dry up, clean up:” operation at the mill. Motors and equipment which had been removed had to be reinstalled. Motors which hadn’t been moved had to be taken out and checked over for damage. Acid from the cleaning house had been carried to the furnaces and had eroded the relays. Dirt, silt and filth was everywhere from the flood waters.

A similar work pattern followed the earlier fires, however, everyone pitched in to get the cleanup job down and the mill back into operations. It was miserable work and at least one man recalls having developed a case of dermatitis then, which lasted for years.

All who remembers the disaster agreed that the flood was a much discouraging disaster in many ways than the fires. After a fire, it is possible to begin immediately to clean up and re-build, however with the food, it’s a case of waiting for the water to recede and the realization that much of the damage from a flood is insidious and only become evident weeks and months later.

Shortly after the flood was past, at noon on March 1, 1938, a span of the Avenue G bridge across the north channel slid into the river. It obviously had been pushed by the ice to the very edge of the pier and finally fell. Fortunately, on one was on the bridge at the time. As a sidelight, The Sterling Gazette newspaper of that date published a report indicating that all the city’s police force were on strike duty at that time.

1906 Ice Jam

The Sterling-Rock Falls community experienced a more serious ice jam problem during the time the Northwestern was operating on the Rock Falls side of the river under the name of the Northwestern Barb Wire Company.

On Feb. 12, 1906, a tremendous ice gorge caused the collapse of the old Avenue G Bridge. The intense pressure of the ice against the old bridge caused the solid iron and stone work to snap after the Rock River peaked on Feb. 12, 1906.

The ice gorge of 1906 jammed the river from Portland and backed it up to Sterling and Rock Falls. The peak was reached when another smaller dam near Dixon broke and sent an additional rush of water downstream towards the area.

The pressure of the ice backed up by the swollen river water washed away three spans of the Avenue G Bridge and shortly thereafter, washed away the north (Sterling side of the river) end of the bridge.

Local officials took immediate steps to re-build the Avenue G Bridge and the work was completed in 1907.

Only Casualty

Northwestern apparently was the only mill casualty during the flood in 1938. Flood water again in 1955 hit a high mark along with a high in February 1973, but at neither date did an overflow occur into the mill itself.

Many other fires have occurred at the mill but none so serous as those in 1928 and again in 1939. Specific operations of the company’s fire protection program is contained in the chapter on Industrial Relations in the history of the Northwestern Steel & Wire Company.

Northwestern Barb Wire Porcupine Barbed Wire

Victorian Advertising Trade Catalog 1888

Northwestern Barb Wire Porcupine Barbed Wire

The following explains in part the secret of the success of our customers in building up and retaining their large trade on our wire: The clear line of difference (look at the cut) between this and other wires enables the dealer and the consumer to avoid confusion, as the close similarity in form of a large number of wires is such that it puzzles an expert to distinguish between them.

We sum up a few of the excellent points in our wire. Possessing in the highest degree all the most desirable features, namely: Strength, Effectiveness, Highest Degree of Economy in Constructions of the Barb.

We sum up a few of the excellent points in our wire. Possessing in the highest degree all the most desirable features, namely: Strength, Effectiveness, Highest Degree of Economy in Constructions of the Barb.

During the Fall of ’87 (1887) we changed and improved all of our machines to use No. 14 for the barb, instead of No. 13 as formerly, ad have shortened the barb. The reduction in size and length gives a barb two inches in length from point to point, and requiring only 1 ¼ inches of wire to make it. This change reduces the weight of Northwestern Barb Wire over 1 ¼ ounces per rod, or about 8 ½ pounds per 100 rods, for our regular cattle wire, making our wire weigh about one pound to the rod.

The Northwestern Wire is lighter by 10 to 20 pounds per 100 rods than many other good barb wires, and does not require the strength to be twisted out of main wires in order to hold the barb in place. The difference in weight by using a No. 14 instead of a No. 13 makes the Northwestern Barb Wire the cheapest as well as the best Barb Wire in the market.

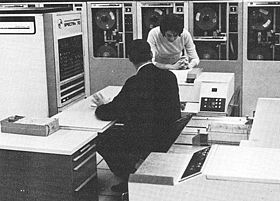

Northwestern Steel & Wire Company Installs New Computer ~ 1967

Retrieved from the Daily Gazette by Dana Fellows ~ 2011

July 6, 1967

Northwestern Steel & Wire Company Installs New Computer

Northwestern Steel & Wire Company has installed a new RCA Spectra 70-25 computer for use in the fields of handling order entry, invoicing systems, production planning, scheduling and inventory controls, and various other fields.

The computer complex consists of the processor, card reader, six tape stations with controller, high speed printer, card punch, and typewriter console. Information is supplied to the complex via punched cards and magnetic tapes.

The third floor of the office annex houses the new computer in a room specifically constructed for this purpose. The room’s temperature and humidity are kept at a constant level, the temperature holding at 70 degrees Fahrenheit and the humidity varying between 45 to 50 percent. In addition Northwestern has a large, excellently trained staff of systems analysts and programmers, along with plans to convert other of the company’s systems to the computer in the near future.

Rolling out Flats – A Specialty at Northwestern’s 14 Inch Mill

Rolling out Flats – A Specialty at Northwestern’s 14 Inch Mill

Retrieved from The Daily Gazette ~ 1979

Transcribed, and minor corrections made, by Dana Fellows ~ 2011

There are over 100,000 uses for the flats that Northwestern Steel and Wire Company produces at the 14 Inch mill. They’re one product that’s used in everything from farm equipment and cars to building construction.

Once the right steel billet or bloom is picked and brought to the correct temperature in a reheat furnace, the work necessary to turn it into a flat begins. The feeder first calls for the billet or bloom from the reheat furnace (whenever the charger adds a billet to reheat furnace, on drops onto the roll line ready to be pulled into the mill stands). The feeder is told by the hot bed operator… the man who controls the cooling bed… exactly when his area can accept another flat.

Once on the roll line, the speed operator, and his helper, is in control working by both, eye and gauge, these two controls the push and pull of the bar by the mill stands which do the actual shaping.

Each mill stand compresses the bar either vertically or horizontally, as the bar’s dimensions are made smaller, its gets longer. The earlier mill stands… called the roughing mills… do more of the work while the stands furthest from the furnace are the finishing stands. These put the final touches on the product such as the exact size, good edges and a nice finish.

The average billet or bloom used in the 14” mill is 32 feet long when it drops from the reheat furnace. By the time it reaches the end of the 375 foot-long line. It can become as long as 400 feet.

Once the bar reaches the proper size and shape, it is rolled onto the cooling bed and comes under the eyes of the hot bed operators, who make sure the flat goes across the bed at a speed that allows it to cool properly, without losing its shape (through bending and warping).

The hot bed hooker then places the flat on the shear roll-line to be cut. The weigher checks customer specifications and tells the shear operator and his helpers what length the customer wants and the sizes of the bundle.

The shear operator cuts the flat and the pieces roll down to the cradle tenders who make up the bundle.

Once cut and bundled, the crane operators place the finished product in piles in the warehouse area by size. It will be shipped according to the customer instructs by the shipping crew, which usually consists of a car checker, hooker loader and the crane operator (who also helps elsewhere in the mill when needed).

During the time the flat is on the roll line, cooling bed, shear line and even just before it is shipped out, the flat is checked and inspected to make sure the customer get the traditional NSW quality product he expects.