No Work Stoppage At Northwestern Steel & Wire Company During Major Floods and Fires Of 1938.

Employees Pitch In To Re-build After Disastrous Flood Of 1938

Retrieved from The Daily Gazette ~ March 13, 1979 Edition

Transcribed, and minor corrections made, by Dana Fellows ~ 2011

Two major fires in 1928 and 1939 along with a flood in 1938 caused extensive damage at te h Northwestern Steel & Wire Company but in all three events, no work stoppage was reported and the employees played an important role in the reconstruction which followed.

Fire is an ever present hazard in a steel mill and the first of the two major fires which hit Northwestern occurred on Friday, May 18, 1928. The fire was a result of some necessary welding from a platform under the wire mill.

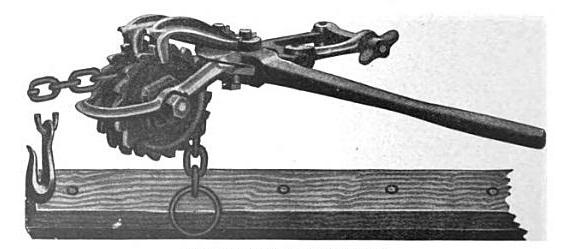

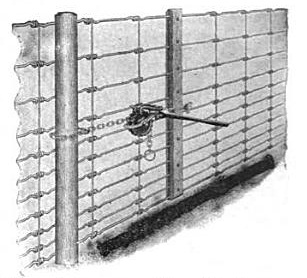

Gears in the fence machines above were driven by shafts which extended down through the floor to the platform . Millwrights would bring barrels of grease from which they would throw grease into the gears as a lubricant. Surplus grease would fall unto the platform and also on the ground below and this waste apparently was not cleaned up.

So, on Friday, May 18, 1928, a torch was being used by welders (Chapman Brothers) set the grease afire. A witness, Gorge Pulford, reported he was coming around a furnace, when, Whoosh!… it went up just like that. Authorities indicated the wind on that particular date helped the fire along.

Pulford recalled that he was one of the several men who turned on hoses where the elevator shaft is now located. “Sandy” Hill and Bert Bradley, chief engineer, also helped with the hoses.

“All of a sudden, there was a big crash, “ Pulford said and added, ‘up on the third floor were these great big furnaces machines, much heavier than the ones we have now. When the floor let loose, down came those machines… boom? We all dropped our fire hoses and ran for the river,…there was no other place to go.”

The fire of 1928 claimed three lives and property damaged estimated at $250,000. The three who lost their lives were working upstairs. One of them would have gotten out safely, but he went back to get his watch in the cleaning house, where the men usually left their watches at that time.

No Work Stoppage

Paul W. Dillon was in Chicago at the time of the fire and when informed, he chartered a plane and returned to Sterling. As he circled over the mill to assess the damage before landing, he obviously was thinking ahead… not bemoaning what was now in the past.

In a report carried in the Sterling Daily Gazette newspaper the afternoon of the fire, it featured a good news item…. “Work for all employees”… contrary to advance reports that the mill would shut down., and the account further indicated., “every employee will be given work and should report Money.”

P. W. Dillon and the mill staff had immediately made the decision to rebuild in the wake of the disaster. In this, as in other emergencies, Northwestern employees were used as a labor supply for the re-construction which followed, rather than bringing in outside help – at least any more than was necessary for specialized work.

During the re-building, office workers also continued at their jobs while the new building was erected and machinery installed. A major changed resulting from the fire was the replacement of water power to the more modern use of electricity supplied from Northwestern’s own steam driven turbines.

A major fire struck northwestern for the second time, 11 years later on Money, March 6, 1939. The 1939 fire started in electric wiring in the bale tie department and was discovered around 6 AM the fire spread and was quickly out of control and reared through the bail tie, barbed wire, machine shop and the galvanizing departments before it was finally checked.

All area firefighting equipment was at the scene including the units from Sterling, Rock Falls and the city of Prophetstown. Firemen fought the blaze despite low water pressure which hampered their efforts. The water used to halt the blaze was pumped from the mill race which still existed although no longer used for power at that time.

Employees near the scene reported seeing the black smoke rolling up as they came to work, then seeing Paul Dillon as he stood in the street directing fire trucks to their locations. No one was injured seriously and the fire was under control by noon.

As in 1928, the decision to rebuild on a larger scale was made before the flames were completely out and that information formed the lead paragraph in the afternoon news report of the fire. It was especially important to get back into production quickly as demand for wire products is heaviest in the spring.

Even though the fire loss was covered by insurance, it was more heart-breaking experience added in other major problems. The 1939 fire came a year after a disastrous flood. The company was still struggling with the adjustment to a unionized work force and had not fully recovered from the financial strains in the installation of the electric furnaces and mills in 1936.

Employees Assist

But, despite the stormy labor relations of the period, men worked night and day shifts to get the mill back into production. The fledging union offered to work one day without pay each week for four weeks to facilitate rehabilitation of the plant but the offer was declined with worm words of gratitude, NS&W President James C. Foster expressed the intention of the management to provide employment for everyone affected by the fire.

Various employees at that time recalled other items in the efforts to rebuild the mill.

By three o’clock in the afternoon of the fire of 1939, a new conveyor had been built over the ruins and was carrying fence to the shipping department for loading.

Two of the bale tie machines were still operable. A tarpaulin was put over them and men kept on working. It was cold; ice froze on the wire coming from the furnaces.

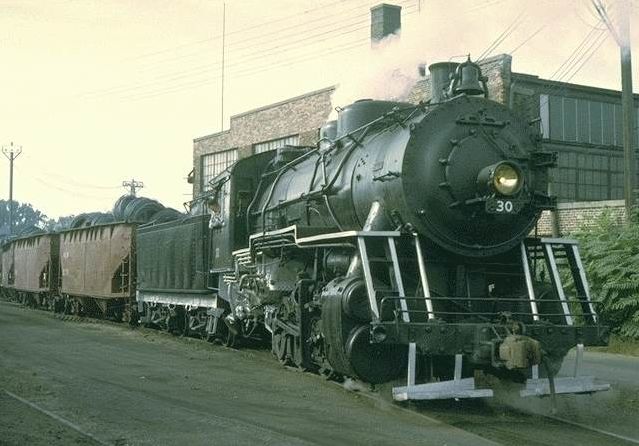

Railroad cranes were used to pick up the damaged machines and transport the equipment to the Parrish-Alford plant in Rock Falls. There the machines were repaired and returned to Northwestern.

As the building frame were up and there were places to set up the machines, they were placed into operation again even though the ends of the buildings were still open, enclosed partially by tarpaulins.

Until the galvanizer could be re-built, galvanized wire was purchased from the American Steel and Wire Company in order that Northwestern customers could be served. But even rebuilding the galvanizer didn’t take too long; as soon as the frame was ready, it was set up and made ready for wire production again.

There was a great deal of improvising. For example, railway car sills were used for columns. Anything available was used to re-build in a hurry and get back into production. Resumption of operations was further speeded up by the loan of a battery of surplus barbed wire machines by Jones & McLaughlin.

The flood of 1938

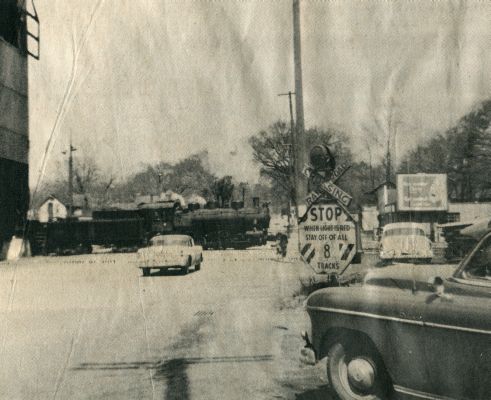

In February of 1938 ice in the Rock River broke up and formed hue jams in tans below the Sterling-Rock Falls area. The ice jams dammed up the already swollen river until water began coming over the retaining wall into the Northwestern plant.

When it became obvious that the mill would be flooded, men began shutting own equipment and pulling up motors. Water along with ice poured into the 10-inch mill and also the furnaces, mold pits, the wire mill and the basement of the office building. Office workers in the basement moved up to the second and third floors but there just wasn’t room for everyone. Elmer Hook recalls coming to work that particular day and seeing his desk out in the middle of the street.

Row boats were the only means of getting around the plant and little could be done until the water receded. One employee recalled seeing some of the men spearing carp, which had been card in the flood water, to an area near the office building.

Efforts were made to dynamite the ice jam without much success; but when the gorge did break loose after a week or so; the water literally went down overnight.

What was left in the wake of the flood was a sickening mess. Mud covered everything. Pools of water stood in all low spots. It was now a “dry up, clean up:” operation at the mill. Motors and equipment which had been removed had to be reinstalled. Motors which hadn’t been moved had to be taken out and checked over for damage. Acid from the cleaning house had been carried to the furnaces and had eroded the relays. Dirt, silt and filth was everywhere from the flood waters.

A similar work pattern followed the earlier fires, however, everyone pitched in to get the cleanup job down and the mill back into operations. It was miserable work and at least one man recalls having developed a case of dermatitis then, which lasted for years.

All who remembers the disaster agreed that the flood was a much discouraging disaster in many ways than the fires. After a fire, it is possible to begin immediately to clean up and re-build, however with the food, it’s a case of waiting for the water to recede and the realization that much of the damage from a flood is insidious and only become evident weeks and months later.

Shortly after the flood was past, at noon on March 1, 1938, a span of the Avenue G bridge across the north channel slid into the river. It obviously had been pushed by the ice to the very edge of the pier and finally fell. Fortunately, on one was on the bridge at the time. As a sidelight, The Sterling Gazette newspaper of that date published a report indicating that all the city’s police force were on strike duty at that time.

1906 Ice Jam

The Sterling-Rock Falls community experienced a more serious ice jam problem during the time the Northwestern was operating on the Rock Falls side of the river under the name of the Northwestern Barb Wire Company.

On Feb. 12, 1906, a tremendous ice gorge caused the collapse of the old Avenue G Bridge. The intense pressure of the ice against the old bridge caused the solid iron and stone work to snap after the Rock River peaked on Feb. 12, 1906.

The ice gorge of 1906 jammed the river from Portland and backed it up to Sterling and Rock Falls. The peak was reached when another smaller dam near Dixon broke and sent an additional rush of water downstream towards the area.

The pressure of the ice backed up by the swollen river water washed away three spans of the Avenue G Bridge and shortly thereafter, washed away the north (Sterling side of the river) end of the bridge.

Local officials took immediate steps to re-build the Avenue G Bridge and the work was completed in 1907.

Only Casualty

Northwestern apparently was the only mill casualty during the flood in 1938. Flood water again in 1955 hit a high mark along with a high in February 1973, but at neither date did an overflow occur into the mill itself.

Many other fires have occurred at the mill but none so serous as those in 1928 and again in 1939. Specific operations of the company’s fire protection program is contained in the chapter on Industrial Relations in the history of the Northwestern Steel & Wire Company.